In the vibrant tapestry of Mexican culture, the state of Yucatán stands out with its rich embroidery traditions, now recognized as intangible cultural heritage by the state government. With around 100 villages boasting their own master embroiderers, both women and men, Yucatán has woven embroidery into its social fabric, symbolizing identity and driving economic vitality.

A Stitch Through Time

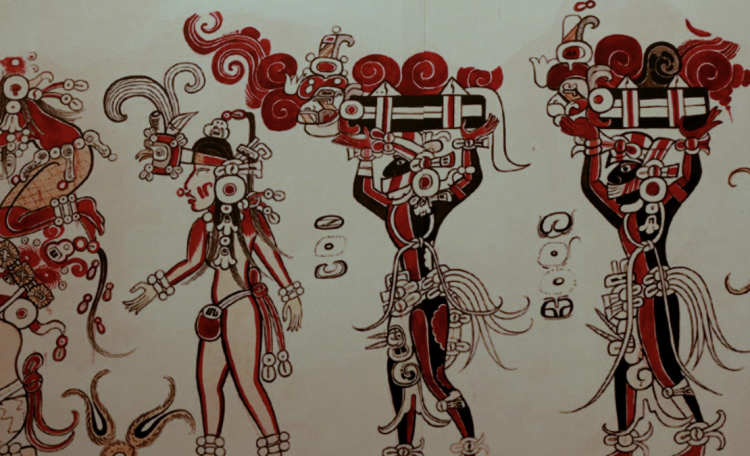

The embroidery of Yucatán has roots that delve deep into history. Restoration experts from the Mexican National Institute of Anthropology and History, such as Rascón, point to archaeological evidence suggesting the craft predates the Spanish colonial period.

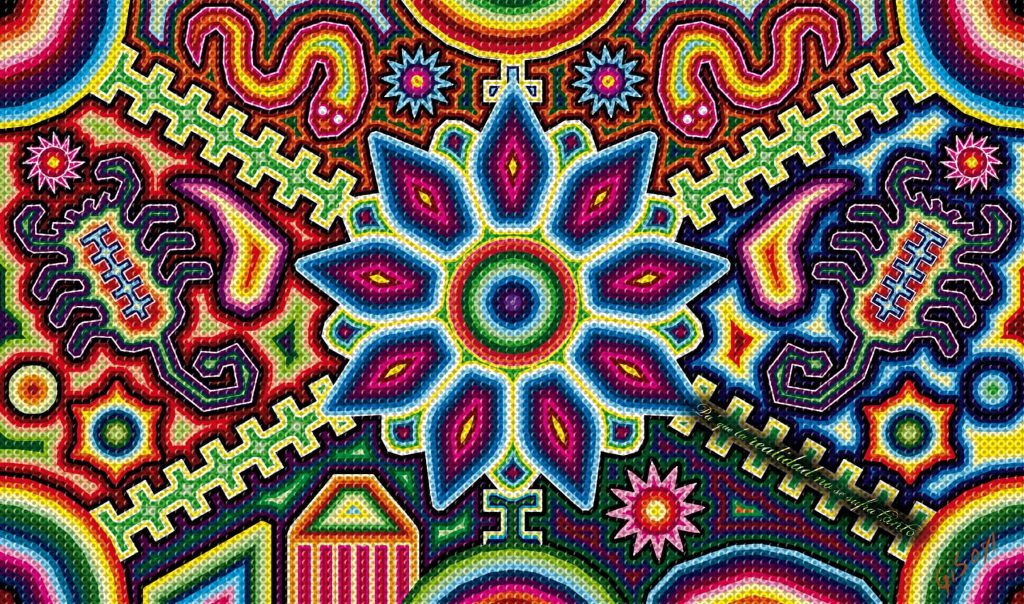

Among the textile techniques unearthed is the satin stitch, unique to Yucatán. Alongside, the serpent stitch, mimicking the scale patterns of a rattlesnake, is found almost exclusively in rural areas. These stitches are among the centuries-old hand embroidery skills that define Yucatán’s artisanal legacy.

The traditional garments, Hipil and Terno, have been worn by the locals since before the colonial era. The Hipil, a tunic created from two or three rectangular pieces of cloth joined by stitching or ribbons and adorned with embroidery, is a common sight. The Terno, an elaborate version of the Hipil, carries the unmistakable stamp of Yucatán’s embroidery, allowing one to trace the “origin” of the piece. Some with a keen eye for the craft can even pinpoint the specific “producing region” based on the embroidery’s style, composition, and color.

Cultural Threads

Embroidery is inextricably linked to the lives of the Maya communities in Yucatán. More than mere decoration, it accompanies Maya men and women from birth to death, holding profound cultural significance.

White embroidered garments mark many of life’s milestones: white Ternos are worn for First Communions and weddings. Silver and golden anniversaries are celebrated in white Ternos, and some celebrants even request their guests to don the same.

During various celebrations and festivals, exquisite embroidery extends beyond attire. For the “Guardian Saint” festivities, people not only wear their finest embroidered clothes but also use embroidered handkerchiefs, napkins, and tablecloths.

The “Holy Cross” festival holds special meaning for the Maya. Crosses are wrapped in beautifully embroidered cloth bursting with colorful floral designs.

The “Food for the Souls” event in November, dedicated to honoring the deceased, sees altars draped in embroidered tablecloths, with corn tortillas, Mexican tamales, and other foods wrapped in lace-embroidered napkins as a sign of respect.

The “Introduction Ceremony” is a unique local ritual welcoming children (boys at four months and girls at three months) into society. Girls typically receive a needle threaded with yarn and are encouraged to touch the sewing machine, a gesture of hope for future embroidery prowess. Boys are urged to touch a machete or gardening tools.

Economic Embroidery

Beyond artistic expression, hand embroidery is a significant source of income for local households. The advent of the sewing machine in the 20th century propelled commercial embroidery, enriching the art with 10 different techniques that blend hand and machine embroidery, with solid-color styles taking precedence.

In 2023, UNESCO launched an initiative to foster economic and social development through Yucatán’s textile arts from a gender perspective, aiming to promote gender equality. The initiative also provided financial and technical assistance to residents to develop local embroidery techniques.