The Hidden Craft of Japan’s Currency

Nestled within the National Printing Bureau of Japan, the sanctum responsible for minting the yen, lies a world shrouded in secrecy and sophistication. The privilege to tour this facility has always been a rare opportunity, becoming exceedingly sought-after with the release of new banknotes—slots filling within an hour of availability each day. A correspondent from the Global Times, through a stroke of luck, secured a spot due to a last-minute cancellation at the Bureau’s Tokyo plant and eagerly submitted the application form.

Given the sensitive nature of the items produced, the tour of the plant is stringent. The reservation phase requires personal information, and on the day of the visit, identification is verified, and a security check is mandatory. Upon entry, all personal items except handkerchiefs and water are to be stored away, with photography permitted only within a designated exhibition hall.

The National Printing Bureau boasts six plants, with the Tokyo facility being one of them. It primarily prints 10,000 and 1,000 yen banknotes, as well as stamps, passports, and the Official Gazette—a publication for national laws and notices.

A Reflection of Modern History

The history of Japanese currency is a mirror to the country’s modern era. In 1868, the Meiji government issued the first nationally recognized government banknote, the “Daikoku Tsuho.” Eiichi Shibusawa, gracing the new 10,000 yen note, was the inaugural head of the Ministry of Finance’s Currency Bureau established in 1871. The simplicity of the Daikoku Tsuho’s production led to rampant counterfeiting, compelling Japan to outsource banknote printing to Germany and the USA. This reliance was costly and politically constraining, prompting the Currency Bureau’s resolve to print domestically.

Lacking experience, Japan’s initial forays into engraving and printing required the costly recruitment of Italian and British experts. In 1881, the first banknote featuring a portrait, crafted by the Italian engraver Edoardo Chiossone, depicted Empress Jingu. The guide shared that, historically, no portraits of Empress Jingu existed, only descriptions of her valor in the “Nihon Shoki.” Thus, Chiossone had to base his design on a female employee at the mint, infusing his imagination into the sketch, resulting in an Empress with an exotic flair on the banknote.

Moreover, a romantic tale is interwoven with this banknote. Chiossone and the female employee developed a bond, and he wished to marry her, facing strong opposition from the head of the Currency Bureau. The couple lived together unwed, and Chiossone, homesick yet unwilling to leave his love, succumbed to melancholy around the age of 50.

Portraits on Banknotes: Chronicles of Japan

The portraits on Japanese banknotes encapsulate the nation’s history, from ancient figures like Sugawara no Michizane, Wakeno Kiyomaro, Fujiwara no Kamatari, and Prince Shotoku—who was featured on six different banknotes over various eras—to modern representatives like Yukichi Fukuzawa, Inazo Nitobe, Soseki Natsume, Hideo Noguchi, Shibasaburo Kitasato, and Eiichi Shibusawa. Female portraits are rare, with Empress Jingu on the first banknote, followed by writer Ichiyo Higuchi and educator Umeko Tsuda.

Exploring the Art of Printing

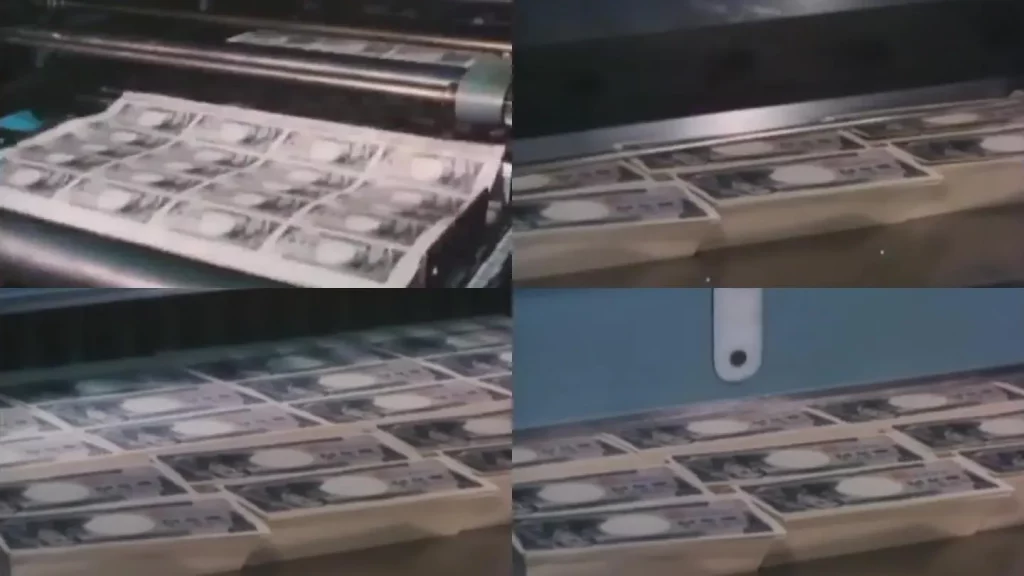

Before entering the plant, guides thoughtfully provided mosquito repellent, cautioning against the abundant insects. Inside, a faint fishy odor—identified by the guide as the unique scent of the printing ink—hung in the air, a smell so distinctive that some new employees resigned within two weeks. Visitors were led to an upper-level corridor overlooking the printing floor through a large frosted glass window. With the press of a button, the glass turned transparent, revealing the meticulous processes of cutting banknotes, applying anti-counterfeit holograms, and numbering, followed by the counting of paper sheets at each stage’s conclusion. The guide recounted how workers were once required to strip and don work attire, reversing the process at day’s end and leaping over a 50-centimeter high bamboo pole to prevent theft—a practice abolished in the 1950s when women were employed and dignity demanded an end to such checks. Now, each step necessitates precise paper counts, with every sheet accounted for before leaving.

The Pinnacle of Anti-Counterfeiting Technology

Japan’s banknote printing technology is advanced, employing special paper processes and anti-counterfeiting measures that are nearly impregnable. Tactile features include intaglio printing and identification marks, while transparency is ensured by high-precision watermarking and striped watermark techniques. The ink not only glows under ultraviolet light but also includes pearlescent ink, which reveals a pink sheen at the center when the note is bent. The guide demonstrated the “tilt method” for verification, particularly the 3D holographic strip that changes the angle of the printed portrait as the note is rotated. Additionally, the new banknotes consider the user’s experience, adding a series of raised diagonal lines to aid the visually impaired in quick identification.

An exhibit within the hall posed the question, “How heavy is 100 million yen?” Displaying the paper used to print 10,000 notes of the 10,000 yen denomination, guesses ranged from 3 to 5 kilograms, with disbelief when informed it was actually 10 kilograms. It appears that while carrying bricks may be burdensome, carrying money never feels like a load.